Cosmic Order and Individual Responsibility

Ma’at (pronounced may-et) is one of ancient Egypt’s most profound philosophical ideals. This principle governs not only human morality but also the structure of the universe itself.

Ancient Egyptians saw Ma’at as the force that upholds the cosmos, guiding celestial and earthly realms alike.

From this perspective, the relevance of Ma’at permeates both the cosmic order and the individual’s role within it, emphasizing that balance within the self reflects and supports balance in the universe.

Table of Contents:

I. Introduction: The Essence of Ma’at

- This section introduces the concept of Ma’at as a fundamental philosophical ideal in ancient Egypt, encompassing both human morality and the structure of the universe. It highlights the interconnectedness between individual balance and cosmic harmony.

II. Ma’at as Cosmic Order

- This section explores the Egyptian belief in a balanced cosmos constantly threatened by disorder (Isfet). Ma’at is presented as the active force maintaining harmony, similar to concepts like yin and yang but personified as a goddess.

- It emphasizes that upholding Ma’at requires continuous effort and vigilance from both gods and mortals to ensure the smooth functioning of cosmic cycles.

III. Human Responsibility in Upholding Ma’at

- This section focuses on the individual’s crucial role in sustaining Ma’at. Every thought, action, and intention contributes to either harmony or disharmony in the cosmos.

- Living in accordance with Ma’at involves embracing truthfulness, compassion, justice, and social responsibility, while rejecting actions that disrupt social and cosmic order.

IV. Ma’at as Inner Equilibrium

- This section delves into the personal dimension of Ma’at, highlighting the importance of inner balance for aligning with the cosmic order.

- It explains the Egyptian belief in the heart as the seat of emotions and intentions and how a pure heart reflects a life lived in balance.

- The afterlife judgment scene, where the heart is weighed against the feather of Ma’at, symbolizes the importance of achieving inner harmony for spiritual advancement.

V. Ma’at and the Collective Good

- This section emphasizes the Egyptian understanding of the interconnectedness between individual actions and the welfare of the community and the cosmos.

- It contrasts the Egyptian focus on collective good with modern individualism, highlighting the belief that every act of kindness or cruelty impacts the overall balance.

- Maintaining Ma’at is presented as a moral and practical obligation, essential for the flourishing of society and the natural world.

VI. Resonance with Modern Life and Psychology

- This section examines the enduring relevance of Ma’at in the modern world, offering a framework for cultivating balance within ourselves and society.

- It connects Ma’at to contemporary psychological concepts of inner equilibrium and purpose beyond individual desires.

- Ma’at’s emphasis on interconnectedness serves as a reminder that individual actions have broader impacts and contribute to collective stability.

VII. Ma’at and the Law of Unity of Opposites: Embracing Cosmic Balance

- This section explores the intersection of Ma’at with the Law of Unity of Opposites, demonstrating how balance arises from the interplay of opposing forces.

- It reinforces the idea that Ma’at is both a principle and a deity, signifying its crucial role in maintaining order and justice within the universe.

- The section further explains how the concept of Isfet, or chaos, underscores the importance of actively maintaining Ma’at.

VIII. Understanding Ma’at: The Principle and the Goddess

- This section delves deeper into the dual nature of Ma’at, exploring both its conceptual and divine aspects.

- It highlights Ma’at’s role as a silent force in times of stability, while also emphasizing its importance as a guiding light during periods of crisis.

- Ma’at’s connection to Ra, the sun god, solidifies its role as a fundamental force in sustaining life and order within the cosmos.

IX. The Law of Unity of Opposites

- This section examines the Law of Unity of Opposites in relation to Ma’at, demonstrating how seemingly opposing forces are interconnected and essential for achieving balance.

- It draws parallels with scientific concepts like Einstein’s theory of relativity, further solidifying the idea that harmony arises from the interplay of opposites.

- The section also emphasizes that tension is necessary for balance, as exemplified by the cyclical relationship between day and night.

X. The Cosmic and Individual Relevance of Ma’at

- This section reiterates the interconnectedness between individual actions and their cosmic consequences, emphasizing the Egyptian belief that living in accordance with Ma’at contributes to universal harmony.

- It highlights specific actions, such as laziness and greed, that disrupt the flow of Ma’at, while underscoring the importance of cultivating positive qualities like compassion and receptiveness.

XI. Ma’at in the Modern World: A Call to Consciousness

- This concluding section reinforces the timeless relevance of Ma’at as a guiding principle for achieving balance in the modern world.

- It calls for conscious effort in promoting balance through our daily choices, emphasizing that acts of compassion and integrity contribute to a just and harmonious world.

- The section leaves the reader with a powerful message: maintaining balance is an ongoing journey requiring constant striving to align with universal principles.

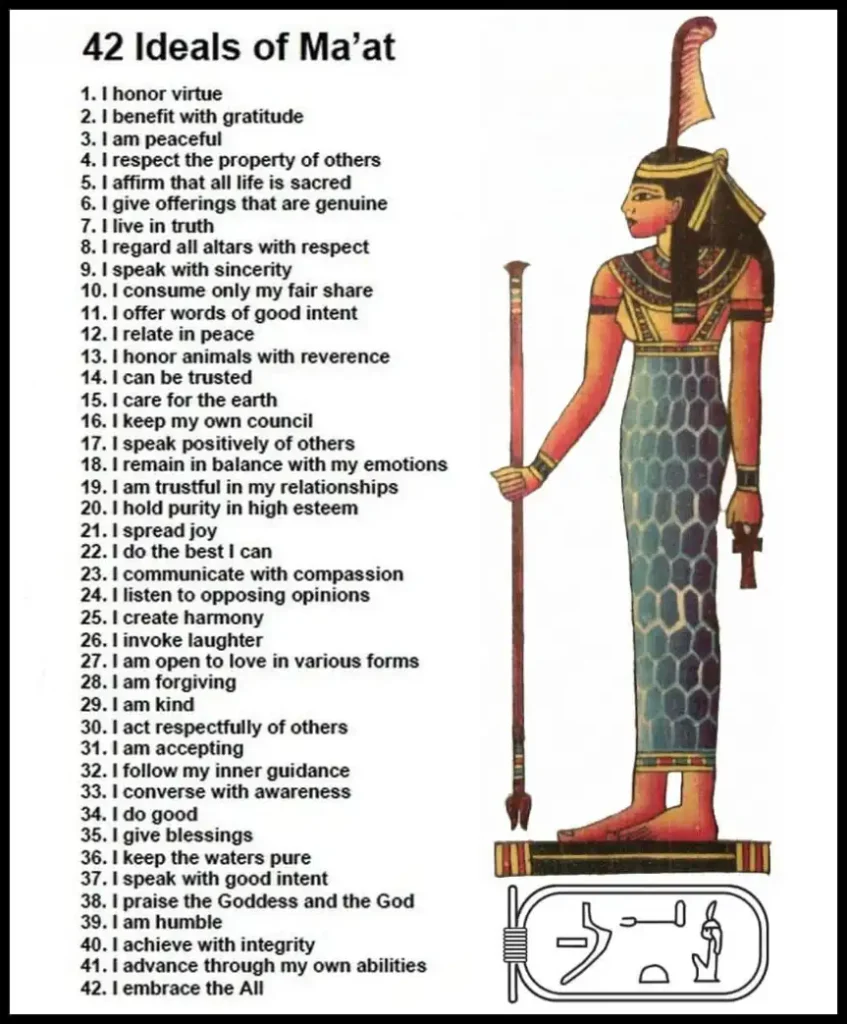

XII. The 42 Laws of Ma’at aka The Negative Confessions

Ma’at as the Cosmic Order

The Egyptians believed that the cosmos was fundamentally balanced, yet it was also in continual danger from disorder, or Isfet. Ma’at stood for the intricate web of relationships between seemingly incompatible elements that kept the universe together.

Other spiritual and philosophical traditions that stress duality and interdependence, such as Taoism’s yin and yang, are similar to this cosmic balancing concept. However, what truly set Ma’at apart was the depiction of a goddess who, along with Ra, ensured cosmic stability as an embodiment of its dynamic divine force, rather than just a concept.

The Egyptians believed that every cosmic entity—from the sun god Ra’s daily journey across the sky to the Nile’s cyclical flooding—operated within the principles of Ma’at. Without Ma’at, the world would succumb to disorder, disrupting the cosmic cycle.

Thus, Ma’at wasn’t merely a passive state of balance; it was an active, ongoing process. Maintaining Ma’at meant continuously striving for harmony, a task that required vigilance, wisdom, and action from both gods and mortals alike.

Human Responsibility in Upholding Ma’at

The individual’s role in sustaining Ma’at was paramount. Ancient Egyptians understood that every thought, action, and intention contributed to the greater harmony or disharmony of the cosmos.

To live according to Ma’at meant living a life of truthfulness, compassion, justice, and social responsibility. Acts of laziness, selfishness, and dishonesty were seen as transgressions against Ma’at because they disrupted the social and cosmic order.

In Egyptian society, Ma’at influenced all aspects of life—from governance to the judiciary system to personal conduct. Pharaohs were considered earthly representatives of Ma’at, tasked with enforcing laws and social norms that upheld balance and justice.

They were expected to embody Ma’at through fair rule, ensuring the well-being of all citizens and the harmony of the land. However, the onus of sustaining Ma’at did not rest solely on the Pharaoh; each individual was responsible for aligning their behavior with Ma’at, contributing to the collective stability and cosmic order.

Ma’at as Inner Equilibrium

The principle of Ma’at was not limited to societal roles; it extended deeply into the individual’s personal life and inner self. To live in accordance with Ma’at required each person to cultivate harmony within their own mind and soul. In this sense, Ma’at parallels what many modern spiritual practices refer to as inner peace or balance.

The Egyptians believed that a person’s heart (the seat of emotions and intentions) should be light and pure, free from the burdens of excess, greed, or malice. When a person’s inner state was balanced, it mirrored the cosmic order, creating a sense of unity between self and universe.

This inner harmony was symbolically represented in the afterlife judgment scene, where a person’s heart was weighed against the feather of Ma’at.

If the heart was as light as the feather, it indicated a life lived in balance and righteousness, allowing the individual to attain maat kheru, or “true of voice,” and enter the afterlife. The feather, representing Ma’at, embodied the pure and unburdened state of being necessary to align with the universal flow.

Ma’at and the Collective Good

The Egyptian focus on Ma’at as a social and cosmic duty reflects a sophisticated understanding of the collective good. Unlike modern notions of individualism, the Egyptians viewed personal actions as inherently connected to the welfare of the community and the cosmos.

Every act of kindness, fairness, and humility contributed to Ma’at; conversely, greed, selfishness, or cruelty chipped away at the balance, inviting Isfet (chaos) into the world.

Thus, Ma’at was not just a matter of personal morality but a commitment to the larger system. The Egyptians saw this commitment as a moral obligation, but it was also practical; without Ma’at, they believed society would descend into anarchy and the natural world would become hostile.

Maintaining Ma’at was akin to nurturing the world itself, ensuring the cycles of life and the continued flourishing of creation.

Resonance with Modern Life and Psychology

In today’s world, the principle of Ma’at can still serve as a powerful reminder of balance, both within ourselves and in society. Living according to Ma’at urges us to consider how our actions impact the world around us and encourages us to cultivate inner peace and harmony.

The principle resonates with the modern psychological focus on achieving equilibrium within the self—managing conflicting emotions, balancing personal ambition with compassion, and seeking purpose beyond individual desires.

Ma’at reminds us that achieving inner balance is not merely a personal quest; it’s a responsibility to the larger world. Our ability to live in harmony with others, to act with integrity, and to promote justice and kindness contributes to the collective stability.

In this sense, Ma’at provides a lens through which we can view our lives as part of a grander cosmic tapestry, where every individual action holds significance.

Ma’at and the Law of Unity of Opposites: Embracing Cosmic Balance

Ma’at stands as a profound and enduring concept that weaves together cosmic balance, harmony, and justice. This principle is more than a mere belief; it is a lived philosophy that ancient Egyptians held as essential to maintaining order in the universe.

But how does this intersect with the Law of Unity of Opposites, a concept suggesting that opposites are inherently interconnected? Together, these ideas guide us toward a deeper understanding of balance as a living, breathing force that operates both within us and in the cosmos at large.

Understanding Ma’at: The Principle and the Goddess

Ma’at holds a dual nature: it is both a principle and a deity. As a principle, Ma’at embodies truth, justice, order, and harmony—qualities seen as essential to sustaining both the physical and spiritual realms. This wasn’t just about personal ethics; it was a cosmological framework.

In times of stability, Ma’at was often assumed as a given, a silent force sustaining the order. However, during periods of crisis, the need for Ma’at was consciously reaffirmed as a guiding light against chaos.

As a goddess, Ma’at personifies these values, symbolizing the active force needed to maintain the cosmic order. She appears as the daughter of Ra, the sun god, illustrating her direct connection to the life-sustaining forces of the universe.

This deification of Ma’at signifies how deeply woven these ideals were into the fabric of Egyptian civilization. Her presence represented a divine endorsement of balance and justice, a commitment to cosmic stability that guided everything from the behavior of individuals to the actions of the Pharaoh, who was seen as the living embodiment of Ma’at.

The Law of Unity of Opposites

The Law of Unity of Opposites suggests that opposing forces are fundamentally interconnected and cannot exist independently. This resonates with how Einstein’s theory of relativity presented mass and energy as equivalent and space and time as intertwined dimensions.

This perspective aligns with Ma’at, which emphasizes balance as something that exists only through the harmonious interplay of opposites. Ancient Egyptians recognized that without Ma’at, chaos or Isfet would prevail, a stark reminder that balance must be constantly maintained through awareness and effort.

This concept also aligns with a fundamental philosophical idea in many traditions: harmony requires tension. Just as day and night rely on each other to define a full cycle, Ma’at requires the ever-present possibility of disorder to underscore the importance of balance.

The Cosmic and Individual Relevance of Ma’at

In Egyptian thought, every individual action had cosmic repercussions. By living in accordance with Ma’at, people weren’t just living virtuously; they were helping to sustain universal order. This ethos fosters a consciousness that extends beyond the self, acknowledging the interconnectedness of all beings.

Laziness, greed, or lack of receptiveness (what the Egyptians called “deafness to Ma’at”) were seen as actions that disrupted the flow of harmony.

Ma’at in the Modern World: A Call to Consciousness

The concept of Ma’at serves as an enduring reminder that balance and harmony require active maintenance, both within ourselves and in society. Just as the Pharaoh performed rituals to maintain Ma’at, we, too, must make conscious efforts in our daily lives to promote balance.

Our choices, from showing compassion to striving for personal integrity, create ripples that contribute to a just and harmonious world.

In the words of Ma’at’s followers, balance is not a destination but a journey—a constant striving to realign with universal principles.

The doctrine of Maat is represented in the declarations to Rekhti-merti-f-ent-Maat and the 42 Negative Confessions listed in the Papyrus of Ani. The following are translations by E. A. Wallis Budge.

42 Negative Confessions (Papyrus of Ani)

The negative confessions one would make after death could be individualized, that is, vary from person to person. These were the confessions found in the Papyrus of Ani:

- Hail, Usekh-nemmt, who comest forth from Anu, I have not committed sin.

- Hail, Hept-khet, who comest forth from Kher-aha, I have not committed robbery with violence.

- Hail, Fenti, who comest forth from Khemenu, I have not stolen.

- Hail, Am-khaibit, who comest forth from Qernet, I have not slain men and women.

- Hail, Neha-her, who comest forth from Rasta, I have not stolen grain.

- Hail, Ruruti, who comest forth from Heaven, I have not purloined offerings.

- Hail, Arfi-em-khet, who comest forth from Suat, I have not stolen the property of God.

- Hail, Neba, who comest and goest, I have not uttered lies.

- Hail, Set-qesu, who comest forth from Hensu, I have not carried away food.

- Hail, Utu-nesert, who comest forth from Het-ka-Ptah, I have not uttered curses.

- Hail, Qerrti, who comest forth from Amentet, I have not committed adultery.

- Hail, Hraf-haf, who comest forth from thy cavern, I have made none to weep.

- Hail, Basti, who comest forth from Bast, I have not eaten the heart.

- Hail, Ta-retiu, who comest forth from the night, I have not attacked any man.

- Hail, Unem-snef, who comest forth from the execution chamber, I am not a man of deceit.

- Hail, Unem-besek, who comest forth from Mabit, I have not stolen cultivated land.

- Hail, Neb-Maat, who comest forth from Maati, I have not been an eavesdropper.

- Hail, Tenemiu, who comest forth from Bast, I have not slandered anyone.

- Hail, Sertiu, who comest forth from Anu, I have not been angry without just cause.

- Hail, Tutu, who comest forth from Ati, I have not debauched the wife of any man.

- Hail, Uamenti, who comest forth from the Khebt chamber, I have not debauched the wives of other men.

- Hail, Maa-antuf, who comest forth from Per-Menu, I have not polluted myself.

- Hail, Her-uru, who comest forth from Nehatu, I have terrorized none.

- Hail, Khemiu, who comest forth from Kaui, I have not transgressed the law.

- Hail, Shet-kheru, who comest forth from Urit, I have not been angry.

- Hail, Nekhenu, who comest forth from Heqat, I have not shut my ears to the words of truth.

- Hail, Kenemti, who comest forth from Kenmet, I have not blasphemed.

- Hail, An-hetep-f, who comest forth from Sau, I am not a man of violence.

- Hail, Sera-kheru, who comest forth from Unaset, I have not been a stirrer up of strife.

- Hail, Neb-heru, who comest forth from Netchfet, I have not acted with undue haste.

- Hail, Sekhriu, who comest forth from Uten, I have not pried into other’s matters.

- Hail, Neb-abui, who comest forth from Sauti, I have not multiplied my words in speaking.

- Hail, Nefer-Tem, who comest forth from Het-ka-Ptah, I have wronged none, I have done no evil.

- Hail, Tem-Sepu, who comest forth from Tetu, I have not worked witchcraft against the king.

- Hail, Ari-em-ab-f, who comest forth from Tebu, I have never stopped the flow of water of a neighbor.

- Hail, Ahi, who comest forth from Nu, I have never raised my voice.

- Hail, Uatch-rekhit, who comest forth from Sau, I have not cursed God.

- Hail, Neheb-ka, who comest forth from thy cavern, I have not acted with arrogance.

- Hail, Neheb-nefert, who comest forth from thy cavern, I have not stolen the bread of the gods.

- Hail, Tcheser-tep, who comest forth from the shrine, I have not carried away the khenfu cakes from the spirits of the dead.

- Hail, An-af, who comest forth from Maati, I have not snatched away the bread of the child, nor treated with contempt the god of my city.

- Hail, Hetch-abhu, who comest forth from Ta-she, I have not slain the cattle belonging to the god.

- The papyrus of Ani; a reproduction in facsimile by Budge, E. A. W. in three volumes.

- Vol. 1 at the Internet Archive (introductory analysis).

- Vol. 2 at the Internet Archive (transcription and translation).

- Vol. 3 at the Internet Archive (facsimile reproduction).

- The Egyptian Book of the Dead.

Sources

- Books:

- Ma’at: The Moral Ideal in Ancient Egypt by Maulana Karenga – An exploration of Ma’at’s principles and moral frameworks.

- Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt by Geraldine Pinch – Provides insights into the role of Ma’at and other Egyptian deities.

- Relativity: The Special and the General Theory by Albert Einstein – Foundational text on the theory of relativity, which aligns with the concept of balance in physical law.

- The Tao of Physics by Fritjof Capra – Discusses the parallels between ancient wisdom traditions (including balance) and modern physics.

- Articles and Academic Journals:

-

“The Tradition of Ma’at in Contemporary Religious Practice” by Merle K Peirce – An examination of the survival of the Egyptian theologicasl concept ma’at in modern Abrahamic and pagan

- “Unity and Opposites in Philosophical Tradition” (in Philosophical Papers) – Explores unity of opposites in various cultural and philosophical contexts.

- “Balance and Reciprocity in Ancient Egyptian Culture” (The Bulletin of the Egyptological Seminar) – An article focusing on Ma’at’s role in balancing cosmic and social forces.

- “Enhancing Wisdom: Ancient Teachings and Philosophies” by Steafon Perry

-

- Web Resources:

- The British Museum’s Ancient Egypt Collection – Offers online resources about Ma’at and Egyptian culture.

- Ancient History Encyclopedia (now World History Encyclopedia): Comprehensive entries on Ma’at, the goddess, and the principle.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Entries on ancient philosophy, cosmic order, and unity of opposites.