Genesis 1 and Babylonian Mythology: Unraveling the Connections

The Genesis creation account has long fascinated scholars and laypeople alike, with its majestic vision of God bringing order from primal chaos in six days of creative work. Yet this biblical text has also been the subject of intense debate, as certain scholars assert that Genesis 1 borrows extensively from the mythology of ancient Babylon.

In this article, I will critically examine the evidence for these alleged literary connections by analyzing the pertinent biblical and Babylonian texts.

Our goal is to gain a deeper, more nuanced understanding of the relationship between Genesis 1 and Babylonian myths like the Enuma Elish through a balanced evaluation of similarities and differences.

What emerges is a complex picture that challenges simplistic notions of direct borrowing. While superficial parallels can be found, closer scrutiny reveals fundamental theological divergences that call into question claims of dependence.

By unveiling the multi-faceted nature of these ancient literary traditions, we can arrive at well-reasoned conclusions about Genesis and its unique vision among the cosmological myths of the ancient Near East.

Exploring the Babylonian Context

Before comparing Genesis 1 to Babylonian myths, we must first understand the context and nature of these non-biblical sources. One of the most significant Mesopotamian texts for our study is the Enuma Elish, an Akkadian epic named after its opening line, “When on high.”

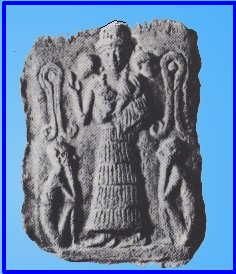

Spanning seven tablets, this epic narrates a cosmogonic myth centered around the rise of the god Marduk and his establishment of cosmic and political order through defeating the goddess Tiamat and her monsters in battle.

The Enuma Elish served an important religious function in Babylon as the basis for the city’s New Year’s festival, the Akitu. During this 12-day festival, priests would ceremonially enact the myth’s drama to renew Marduk’s kingship and affirm Babylon’s status as the highest deity’s sacred city.

As a product of Babylonian scribal schools meant to reinforce theology and ideology, the text emphasized Marduk’s supremacy over other gods like Anu and Ea through his creative acts.

Beyond the Enuma Elish, Mesopotamian scholarship has uncovered numerous fragments of cosmological myths among tablets from places like Nippur and Uruk, indicating a diversity of creation traditions existed across ancient Mesopotamia.

While some scholars assert Genesis borrowed from a single source like the Enuma Elish, the evidence suggests Genesis may have interacted with or adapted elements from a wider body of Mesopotamian myths.

With this context in mind, we can now examine Genesis 1 in light of Babylonian mythology to analyze purported connections and divergences between the two traditions.

-

Marduk and Zeus have a number of features in common, especially as Zeus emerges as lord of the cosmos.

-

Kronos is very much a Qingu-like figure, especially in his battles with Ouranos, and as he emerges as lord of the cosmos.

-

Likewise, there are parallels between Ti’amat of Enuma Elish and Gaia, who stirs up her children—the Titans—against their father.

Enuma Elish (abbrv)

Tablet I

1. When in the height heaven was not named,

2. And the earth beneath did not yet bear a name,

3. And the primeval Apsû, who begat them,

4. And chaos, Tiamat, the mother of them both,–

5. Their waters were mingled together,

6. And no field was formed, no marsh was to be seen;

7. When of the gods none had been called into being,

8. And none bore a name, and no destinies [were ordained];

9. Then were created the gods in the midst of [heaven]

(All gods, monsters, and other characters are celestial orbs, sometimes known as planets, dwarf planets, and moons. Tiamat was the largest planet, although Apsu, her counterpart, could still compete with the younger gods (planets). Their “waters mingling” might refer to a collision, the seeding of life on the other, or the drawing of more things into their orbit.”)

Tablets II – III

To recapitulate, these tablets detail the rising conflict between the gods and their progeny, as well as the arrival of the Supreme God, Marduk.

(The arrival or birth of these additional planetary bodies (Gods) from Tablet I results in several planets surrounding Tiamat and Apsu, most likely hurling debris at them and appearing to be a nuisance. Then a rogue planet known as Marduk enters the newly formed Solar System.)

Tablet IV

9. “Established shall be the word of thy mouth, irresistible shall be thy command;

10. “None among the gods shall transgress thy boundary.

11. “Abundance, the desire of the shrines of the gods,

12. “Shall be established in thy sanctuary, even though they lack (offerings).

13. “O Marduk, thou art our avenger!

14. “We give thee sovereignty over the whole world.

30. They give him an invincible weapon, which overwhelmeth the foe.

31. “Go, and cut off the life of Tiamat,

34. They caused him to set out on a path of prosperity and success.

47. He sent forth the winds which he had created, the seven of them;

93. Then advanced Tiamat and Marduk, the counsellor of the gods;

94. To the fight they came on, to the battle they drew nigh.

100. And her courage was taken from her, and her mouth she opened wide.

103. He overcame her and cut off her life;

Tablet V

1. He.(i.e. Marduk) made the stations for the great gods;

2. The stars, their images, as the stars of the Zodiac, he fixed.

3. He ordained the year and into sections he divided it;

4. For the twelve months he fixed three stars.

5. After he had […] the days of the year […] images,

6. He founded the station of Nibir to determine their bounds;

7. That none might err or go astray,

8. He set the station of Bêl and Ea along with him.

9. He opened great gates on both sides

10. He made strong the bolt on the left and on the right.

11. In the midst thereof he fixed the zenith;

12. The Moon-god he caused to shine forth, the night he entrusted to him.

13. He appointed him, a being of the night, to determine the days;

14. Every month without ceasing with the crown he covered(?) him, (saying):

15. “At the beginning of the month, when thou shinest upon the land,

16. “Thou commandest the horns to determine six days,

17. “And on the seventh day to [divide] the crown.

(During Marduk’s trips across the solar system, it dragged planets and moons into their orbits, fixing their stations.).

Tablet VI contains a passage from The Atrahasis Epic on the genesis of man. Tablet VII depicts Marduk’s time of leisure and joy after creating the heavens and earth. Marduk permits everyone to rest on the seventh tablet, just as God did on the seventh day.

Comparing Key Themes and Motifs

On a basic level, both Genesis 1 and myths like the Enuma Elish share certain cosmological themes, addressing questions about the origin of the cosmos and humanity. Both also feature elemental motifs of primeval waters and a transition from chaos to order. Yet upon closer scrutiny, their theological emphases and conceptual frameworks differ markedly.

One major disparity lies in their treatment of divinity. The Enuma Elish revolves around conflicts between gods, personifying natural forces as they establish dominance. Genesis, meanwhile, emphasizes a singular, transcendent Creator God who brings the cosmos into being through divine fiat or command. Polytheism characterizes Babylonian mythology, but Genesis upholds strict monotheism.

Related to this is Genesis’ lack of any divine conflict or generation mythology. While myths like the Enuma Elish focus on the genealogies of gods and their wars, Genesis centers peacefully on creative divine fiat alone. Its vision stands apart from notions of gods emanating from one another through violent means inherent to polytheism but foreign to biblical theology.

Genesis also diverges in its presentation of humanity. The Enuma Elish depicts humans as afterthoughts created from divine blood and clay to serve the gods. But Genesis portrays humanity as the pinnacle of creation, made in God’s image to have dominion. Far from tools for gods, people stand as God’s beloved representatives.

The Scripture’s Authority

The supposed authority of the Old Testament is in jeopardy. Doesn’t Neo-Darwinism destroy both the historical and symbolic significance of Genesis 1, converting it to the worst kind of myth? Is it true that God’s creation was “very good” according to Genesis 1? Was it “excellent” when finished? Or was it a never-ending torture chamber of millions of years of sickness, death, cheating, and corruption that eventually resulted in something nice but wasn’t?

Wouldn’t such benevolence in Genesis be a terrible kind of symbolism? Were all of these seemingly evil things, as Neo-Darwinists confidently maintain, actually creation tools? Is it true that there was a good creation, a paradise, and a fall? Or is this all part of the make-believe package, which promises that none of this matters as long as we remember that God stood at the beginning of everything at some point? What kind of god is he, and does he even exist? If that’s the case, isn’t he a monster, akin to the ancient Demiurge?

How one interprets Genesis has an impact on the New Testament and its authority. Luke is regarded as a world-class historian. But isn’t it Luke who claims to be giving his readers a true historical family history of Jesus? (KJV, Luke 3:23–38)

And Jesus himself began to be about thirty years of age, being (as was supposed) the son of Joseph, which was the son of Heli,

24Which was the son of Matthat, which was the son of Levi, which was the son of Melchi, which was the son of Janna, which was the son of Joseph,

25Which was the son of Mattathias, which was the son of Amos, which was the son of Naum, which was the son of Esli, which was the son of Nagge,

26Which was the son of Maath, which was the son of Mattathias, which was the son of Semei, which was the son of Joseph, which was the son of Juda,

27Which was the son of Joanna, which was the son of Rhesa, which was the son of Zorobabel, which was the son of Salathiel, which was the son of Neri,

28Which was the son of Melchi, which was the son of Addi, which was the son of Cosam, which was the son of Elmodam, which was the son of Er,

29Which was the son of Jose, which was the son of Eliezer, which was the son of Jorim, which was the son of Matthat, which was the son of Levi,

30Which was the son of Simeon, which was the son of Juda, which was the son of Joseph, which was the son of Jonan, which was the son of Eliakim,

31Which was the son of Melea, which was the son of Menan, which was the son of Mattatha, which was the son of Nathan, which was the son of David,

32Which was the son of Jesse, which was the son of Obed, which was the son of Booz, which was the son of Salmon, which was the son of Naasson,

33Which was the son of Aminadab, which was the son of Aram, which was the son of Esrom, which was the son of Phares, which was the son of Juda,

34Which was the son of Jacob, which was the son of Isaac, which was the son of Abraham, which was the son of Thara, which was the son of Nachor,

35Which was the son of Saruch, which was the son of Ragau, which was the son of Phalec, which was the son of Heber, which was the son of Sala,

36Which was the son of Cainan, which was the son of Arphaxad, which was the son of Sem, which was the son of Noe, which was the son of Lamech,

37Which was the son of Mathusala, which was the son of Enoch, which was the son of Jared, which was the son of Maleleel, which was the son of Cainan,

38Which was the son of Enos, which was the son of Seth, which was the son of Adam, which was the son of God.

If Adam was a fable, where does Luke cease to be an excellent historian in this genealogy? Wasn’t he a little hasty in referring to Moses as the originator of the Torah (16:31, 24:44)?

Wouldn’t that be weird for someone who is said to have met and talked with Moses (9:28-36)?

Or was Luke portraying a Jesus who adopted the ignorant conventions of his time, or, perhaps, who did not know any better himself (kenosis theology) and as a result confirmed people in their ill-founded literalistic approach of Genesis stories like the one about Sodom and Gomorra (Luke 10:12), Lot (Luke 17:28-30), even Lot’s wife turning into a pillar of salt (Luke 17:32), not to mention Noah and the Ark (Luke 17:26-27, cf. 3:36)?

If Genesis 1–11 is a creation of well-meaning religious Jews during the Babylonian exile, and if it is basically mythological in nature, it should have ramifications for how the New Testament is interpreted as history as well.

Luke has a ‘literalistic’ view of Genesis. With someone thus uneducated (in terms of Dickson’s thesis), how can one rely on the historical nature of his supernatural accounts? For example, in Luke, Jesus raises the widow’s son (7:11–17) and Jarus’ daughter (8:40–56). What about Jesus’ own resurrection (Luke 24)?

One could argue that Jesus is all about overcoming spiritual death and that questioning the historical nature of the miracles and mythological parallels is simply stupid literalism. Luke did not want to preach that Jesus was a direct descendant of Adam, Noah, and Shem. He also did not want his readers to assume that all of the ‘fanciful’ things he told about Jesus’ life were true.

Luke simply wanted to convey that he thought Jesus was a lovely guy who was still spiritually present in the lives of individuals he touched. Luke is simply expressing gratitude in his pre-scientific manner, just as Genesis only tries to demonstrate that God existed in the beginning.

Key Differences in Literary Form and Intent

Beyond divergences in theological themes, Genesis 1 differs substantially from the Enuma Elish and other myths in its literary form and purpose. Scholars classify the Enuma Elish primarily as a “theogony” focused on establishing a divine genealogy and politics. Genesis, by contrast, fits the category of “cosmogony,” centered on describing God’s ordered creative work.

Genesis lacks the Enuma Elish’s political agenda of elevating Marduk and Babylon. It carries no trace of serving ritual drama or reinforcing a city-god’s supremacy. Genesis simply and sublimely recounts God’s creation in a way free of mythology’s convoluted narratives driven by other motives.

Genesis also follows a unique and precise literary structure of six days of creative work plus a seventh day of rest. No Mesopotamian myth mirrors this pattern. While some propose it reflects the week-long format of the Akitu, direct dependence seems unlikely given the substantial theological divergences between the works. More plausibly, Genesis innovated a new form emphasizing God’s completion and blessing of the Sabbath.

Challenging Notions of Direct Literary Borrowing

When examining purported connections in light of these very real differences, the notion of Genesis 1 directly borrowing from the Enuma Elish or related myths becomes problematic. On the levels of theology, concepts, literary style, and religious function, the works diverge too fundamentally to suggest simple literary appropriation.

Genesis may have engaged ancient Near Eastern traditions generally as it formulated its unique outlook, but the evidence does not support reducing Genesis to a derivative reworking of Babylonian literature. Its message stands too singular, focused on proclaiming God’s good creation and humankind’s place within it rather than perpetuating mythology’s aims.

What’s more, as historian K.A. Kitchen and others argue, both biblical and Mesopotamian cosmological texts originated much earlier—during the late third and early second millennia BC—than the typical proposed borrowing date of the Babylonian exile in 587–539 BC. Genesis took shape independently from its ancient context, not as a late response to it.

Conclusion: An Independent yet Engaging Account

In conclusion, while Genesis 1 shares broad cosmological concerns with ancient Near Eastern myths, close analysis shows its conception of God and creation, a distinctive theological framework, innovative literary form, and early origins point to its independence from any single extra-biblical influence like the Enuma Elish.

At the same time, Genesis’ engagement with and divergence from the widespread mythical traditions of its cultural environment demonstrate its author(s) creatively adapted ancient motifs to proclaim a radically new revelation – that of one transcendent Creator God whose good creation and relationship with humanity stand in stark contrast to polytheism’s conceptual world.

Far from derivative borrowing, Genesis offers an inspired transformation and prophetic correction of the ancient myths. Its message endures as a foundational framework for understanding God, humanity, and our purpose within creation.

References

-

In recent years, this view has been popularised in evangelical circles in Australia through such as John Dickson, The Genesis of Everything, ISCAST Journal for Christians in Science and Technology v.4, pp.1–18, 2008, and John Dickson, Greg Clark and Simon Smart, God Science: Creation, Darwin And The End Of Faith, (DVD), Centre for Public Christianity, 2010.

-

Greek text online: khazarzar.skeptik.net/books/philo/decalogg.pdf

-

Greek text online: khazarzar.skeptik.net/books/philo/decalogg.pdf

-

Philo refers to the period of the creation week as a whole, which in Genesis 1 included God’s subsequent rest and satisfaction.

-

Greek text online: khazarzar.skeptik.net/books/philo/decalogg.pdf

-

In the Old Testament earth days are not always of equal length, e.g. Joshua 10:12 and Isaiah 38:8.

-

For a good contemporary English translation see Stephanie Dalley, Myths from Mesopotamia, Oxford, pp.233–77, 1988.

-

Dalley, ref. 2, p.273.

-

S. Dalley, ref. 2, p.230. She further remarks that some Amorite deity, rather than Marduk, may have been the original hero of the epic.

-

Some may object that in Genesis 2:7 Yahweh is a fashioner also, but two important points need to be made here: (i) the “dust of the earth” does not come from a dead god, as in Enuma Elish; (ii) there is no hint in Enuma Elish that Marduk “breathes into man the breath of life”, as in Genesis 2:7.

-

K.A. Kitchen, The Bible in its World, Paternoster, pp.34–35, 1977.

-

See Hugh G. Evelyn-White (tr.), The Theogony of Hesiod, http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/hesiod/theogony.htm, accessed 14.3.2013.

-

For example, Justin Martyr, Discourse to the Greeks, III; in Ante-Nicene Fathers, Eerdmans, p.272, 1967.

-

See, e.g. D.L. Ashliman, The Norse Creation Myth, http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/creation.html, accessed 14.3.2013. A search on the Internet will reveal several versions of the Norse myths.