Understanding the Complexity of Ancient Civilizations

Before European contact, the Americas were far from a “New World”; they were instead a diverse continent of thriving cultures and societies.

This article takes an expansive look at pre-Columbian civilizations across regions including the Caribbean, Middle America, the Andes, the South Atlantic, and North America.

By examining each area’s unique developments in agriculture, social structure, and innovation, we gain insight into the intricacies of these ancient cultures.

The Caribbean: Island Cultures and Complex Societies of the Taínos and Caribs

In the Caribbean, the Taíno and Carib peoples developed distinct societies influenced by their island environments, leading to both cooperation and conflict.

The Taíno occupied major islands such as Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, creating a hierarchical society based on agriculture and fishing. Known for cultivating cassava and corn, Taíno farmers utilized raised beds and other methods suited to tropical soils.

Their agricultural efficiency supported populous villages led by chiefs called “caciques.” These leaders played key roles in both ceremonial life and everyday governance, cementing a structured social organization.

On the smaller islands, the Carib people took a more nomadic approach, focusing on fishing and sea travel. Renowned as skilled navigators, they crafted large dugout canoes that allowed extensive trade and exploration across the Caribbean Sea.

The Caribs’ movement and reputation as fierce warriors often created tension with the Taíno, illustrating an early example of intercultural dynamics in the Americas.

The Taíno and Carib people inhabited the Caribbean islands, each developing unique ways of life shaped by their environments.

Taíno Society and Agricultural Innovations

- The Taíno cultivated cassava, corn, sweet potatoes, peanuts, and cotton. Cassava, a highly resilient crop, was central to their diet, and they processed it to remove toxins.

- They also developed mound agriculture, a method in which crops were grown on raised beds to improve soil drainage and fertility. This technique suited the wet, tropical climate and enabled a stable food supply.

Social Organization and Governance

- The Taíno society was organized hierarchically, with “caciques” (chiefs) who wielded authority over their communities. Caciques held both political and religious authority, guiding public life and ritual practices.

- The Taíno practiced a unique spiritual system known as “zemiism,” wherein carved stone or wooden idols, called “zemis,” were worshipped as spirits of ancestors or deities.

Carib Sea Navigation and Warrior Society

- Renowned for their navigational skills, the Carib people were adept sailors who navigated open waters using large dugout canoes. These canoes could hold up to 50 people and were used for fishing, trade, and raids on other islands.

- The Carib warrior society emphasized strength and valor. Their warrior reputation often led to conflicts with the Taíno, who lived on the larger islands. These encounters reveal an early example of intercultural dynamics and tension.

References: Wilson, S. M. (1997). The Indigenous People of the Caribbean. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

1492: An Ongoing Voyage,” Library of Congress; Wilson, S. M. (1997).

Middle America: The Aztecs and Mayans’ Contributions to Civilization

Middle America, with its towering Maya temples and busy Aztec metropolis, was home to some of the Americas’ most accomplished civilizations. The Maya, inhabiting parts of present-day Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras, were master builders and astronomers.

Known for their stone pyramids, they built monumental city-states like Tikal and Copán, each governed independently but connected through trade. They also established a sophisticated writing system based on glyphs, one of the earliest known in the Americas.

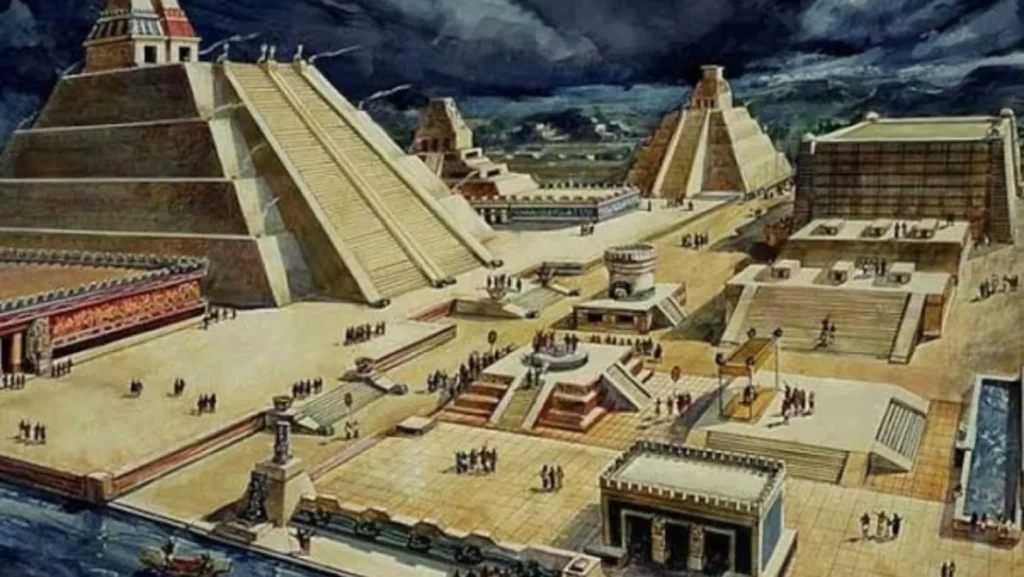

The Aztecs, arriving later, established their capital, Tenochtitlan, on an island in Lake Texcoco. This engineering marvel was built on a series of man-made islands connected by causeways.

Using a combination of tributes and an extensive trade network, the Aztecs controlled a powerful empire stretching from the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific. Rituals, including human sacrifice, were integral to their religious beliefs, meant to appease gods and maintain cosmic balance.

In Middle America, the Aztec and Maya civilizations rose to prominence, each contributing foundational advancements to architecture, mathematics, and governance.

Maya Civilization: Architecture, Astronomy, and Writing

- The Maya are celebrated for their towering pyramids and expansive city-states like Tikal, Copán, and Palenque. These cities served as ceremonial centers with pyramids that aligned astronomically.

- Their expertise in astronomy allowed them to create highly accurate calendars. They recognized cycles of Venus and tracked lunar phases, which informed both agricultural and ceremonial practices.

- The Mayan script, a complex system of glyphs, is one of the few indigenous writing systems of the Americas. It records historical events, including wars and alliances, on stone monuments known as stelae.

Aztec Empire: Tenochtitlan, Empire Building, and Religious Practices

- Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, was built on Lake Texcoco, featuring floating gardens (chinampas) that allowed year-round cultivation.

- The Aztecs established an extensive tribute system in which conquered territories provided resources, crafts, and soldiers. This tribute supported the Aztec nobility and funded large-scale building projects.

- The Aztec religion held that sacrifices were necessary to appease the gods. Priests played a central role, and temples such as the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan were built for these rites, symbolizing the empire’s commitment to cosmic balance.

References:Indigenous America. Authored by: Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, with content contributions by L. D. Burnett, Michelle Cassidy, D. Andrew Johnson, Joseph Locke, Dawn Marsh, Christen Mucher, Cameron Shriver, Ben Wright, and Garrett Wright.

The Andes: The Inca Empire’s Architectural and Agricultural Prowess

The Inca Empire, sprawling across the Andes Mountains, exemplified resilience in the face of challenging geography. The Incas’ terraced farms enabled agriculture in high altitudes, where they grew potatoes, quinoa, and maize on carved mountainsides, ensuring food security for their vast empire.

They developed irrigation canals and storage systems to manage resources efficiently, forming a complex society based on cooperation and reciprocity, known as “ayllu.”

In terms of architecture, the Incas left behind monumental sites like Machu Picchu, demonstrating advanced masonry skills that required no mortar. Roads and bridges spanned across steep mountains, linking distant parts of the empire, while messenger runners—called “chasquis”—carried information across long distances in record time.

Spanning modern-day Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, and parts of Chile and Argentina, the Inca Empire was defined by its sophisticated social organization and engineering feats.

Agricultural Innovations and Resource Management

- The Incas implemented terracing to transform steep Andean slopes into fertile farmland, thus maximizing arable land in mountainous regions. They cultivated diverse crops, including over 3,000 varieties of potatoes.

- They also developed an intricate irrigation system with aqueducts and reservoirs, which allowed them to grow crops at high altitudes.

- Storage facilities, or “qollqas,” were strategically built along roads for grain and food storage, enabling the Incas to withstand droughts and shortages.

Architecture and Communication

- Incan architecture, exemplified by sites like Machu Picchu, employed precise stone-cutting techniques, creating structures that have withstood earthquakes for centuries.

- The Incas established an extensive road network stretching over 25,000 miles, which connected distant regions of the empire. Messenger runners, or “chasquis,” relayed messages across these roads, ensuring effective governance.

References: D’Altroy, T. N. (2014). The Incas. Wiley-Blackwell.

Moseley, M. E. (1992). The Incas and Their Ancestors

The Archaeology of Peru. Thames & Hudson; D’Altroy, T. N. (2014). The Incas. Wiley-Blackwell.

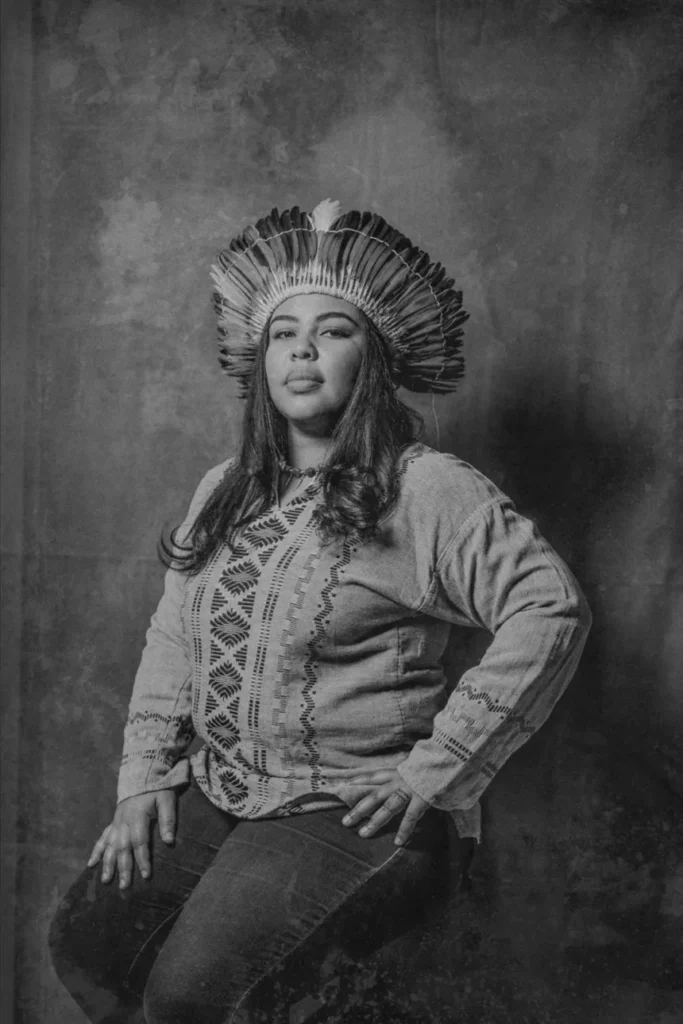

South Atlantic: The Tupi and Tapuya of Eastern South America

In Eastern South America, particularly within modern Brazil, the Tupi-speaking people crafted a society rooted in agriculture and riverine resources. Living in large communal houses called “malocas,” Tupi communities practiced slash-and-burn farming to grow cassava and maize, supplemented by fishing and hunting.

The Tupi also shared unique cultural practices, including a form of ritual warfare that symbolized strength and valor within their society.

The Tapuya, on the other hand, led more nomadic lives in the hinterlands. While the Tupi largely embraced agrarian society, the Tapuya were known as hunter-gatherers. This contrast in lifestyles between the two societies reflects the adaptability and diversity of pre-Columbian cultures even within the same region.

In Middle America, the Aztec and Maya civilizations rose to prominence, each contributing foundational advancements to architecture, mathematics, and governance.

Tupi Agricultural Society and Cultural Traditions

- The Tupi developed “slash-and-burn” agriculture, a method that involved clearing forested areas to cultivate cassava and maize. This sustainable approach allowed for soil regeneration over time.

- They lived in large communal houses known as “malocas,” which housed extended family units, fostering community cohesion.

- Ritualistic warfare was central to Tupi culture, symbolizing bravery and reaffirming social bonds. These conflicts also played a role in the practice of ritual cannibalism, which symbolized the transfer of warrior strength.

The Tapuya: Hunter-Gatherer Adaptations

- Unlike the Tupi, the Tapuya were primarily hunter-gatherers, relying on fishing, hunting, and wild plants. This more nomadic lifestyle differentiated them significantly from the agricultural Tupi.

- Their adaptability to diverse ecosystems, from riversides to forests, underscores the ecological diversity of ancient South American societies.

References: Hemming, J. (2004). Red Gold: The Conquest of the Brazilian Indians. Harvard University Press.

Fausto, C. (2012). Warfare and Shamanism in Amazonia. Cambridge University Press; Hemming, J. (2004).

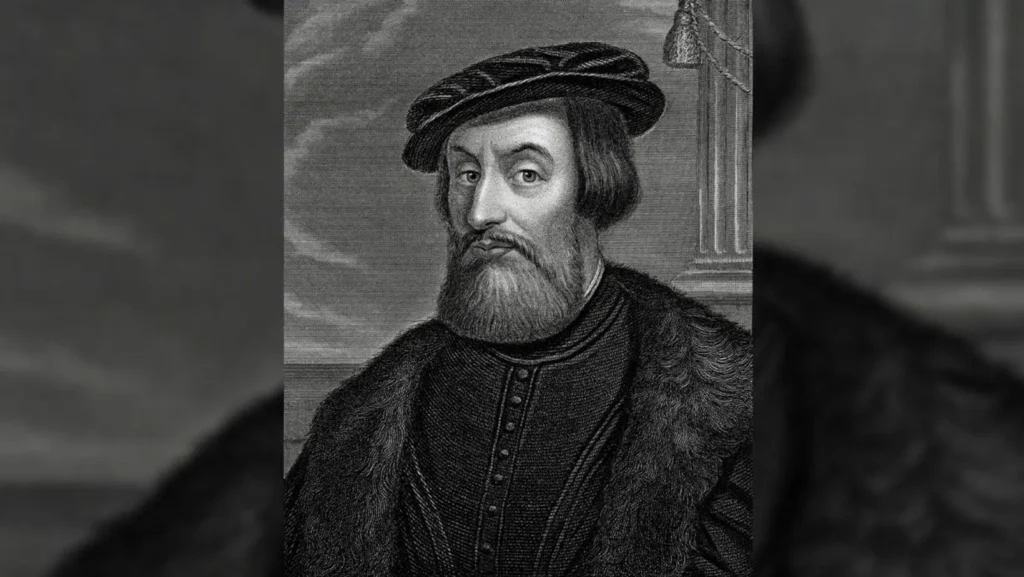

Hernán Cortés: A Enzyme for Change

Drawn Diseases: An Invisible Enemy

Diseases like smallpox have no precedent among Indigenous peoples; their immune systems were equipped for such outbreaks.

That produces Some estimates show up to ninety percent population decreases in some areas—a astounding figure that underscores how biological considerations factored into colonial dynamics almost as much as fighting did.

This bleak reality transformed demographic landscapes considerably over time, finally providing place even for settlers from other regions of Europe looking to start colonies again and leave a ghost town behind.

References: Baker, Kevin (October 2005). “1491′: Vanished Americans”. The New York Times. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

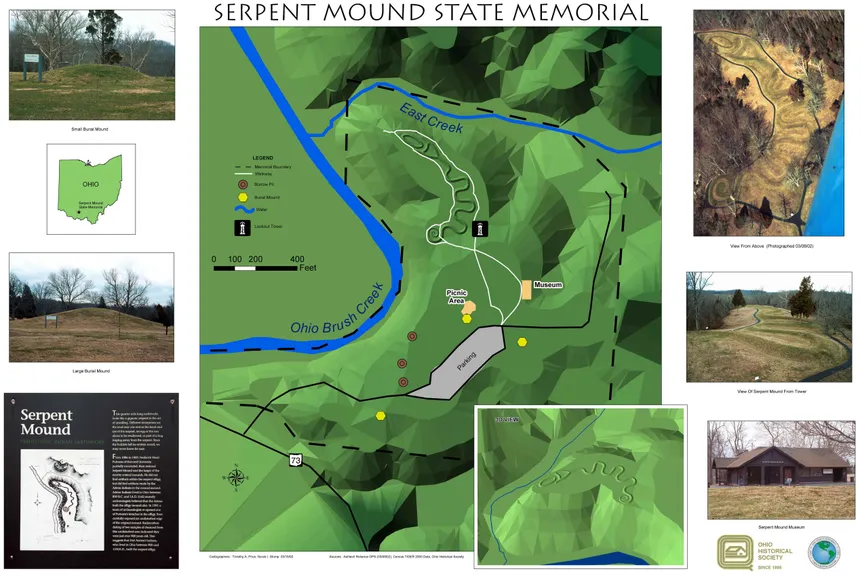

North America: Societal Complexities from the Great Lakes to the Plains

In North America, societies such as the Iroquois Confederacy of the Northeast and the Pueblo cultures of the Southwest demonstrated adaptability and community governance long before European contact.

The Iroquois formed a confederacy among five nations, practicing a sophisticated democratic council system that influenced American ideals of governance.

Their “Three Sisters” agricultural technique—growing beans, corn, and squash together—was ecologically sound and maximized crop yields.

Indigenous societies across North America demonstrated remarkable ecological knowledge and developed systems of governance that have inspired modern democratic ideals.

Iroquois Confederacy: Republic Governance and Agricultural Practices

- The Iroquois, or Haudenosaunee, formed a confederation of five nations governed by a council that encouraged peaceful resolution of disputes. This system later influenced early American democratic structures.

- Their “Three Sisters” agricultural method, planting corn, beans, and squash together, provided balanced nutrition and maintained soil fertility through nitrogen-fixing legumes.

Pueblo Cultures: Architectural Resilience and Environmental Adaptation

- In the arid Southwest, the Pueblo people constructed multi-storied adobe dwellings and cliffside villages, which offered protection against harsh weather and potential invaders.

- Pueblo farmers developed advanced irrigation systems to channel water from rivers and springs to their fields, a necessity in the desert landscape.

Plains Cultures: Adaptation to Grassland Environments

- Tribes such as the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Comanche adapted to the Great Plains, developing a culture centered on bison hunting. These nomadic tribes followed bison herds, and their society revolved around communal hunting practices.

- The Plains cultures perfected the tipi, a portable shelter suited to their migratory lifestyle, demonstrating innovation in harmony with their environment.

References: Discovering the Hidden Gems of Ancient Civilizations by Steafon Perry

Fenton, W. N. (1998). The Great Law and the Longhouse: A Political History of the Iroquois Confederacy. University of Oklahoma Press.

Conclusion: Preserving and Learning from America’s Ancient Cultures

The legacy of pre-Columbian societies is vast, encompassing advances in science, engineering, governance, and spirituality that continue to fascinate historians and archaeologists. Through studying their achievements, we gain insights into human adaptability, resilience, and creativity.

By recognizing the complexities of these societies, we honor the ingenuity and diversity of the Americas’ original inhabitants, whose contributions have left an enduring mark on global history.