Introduction

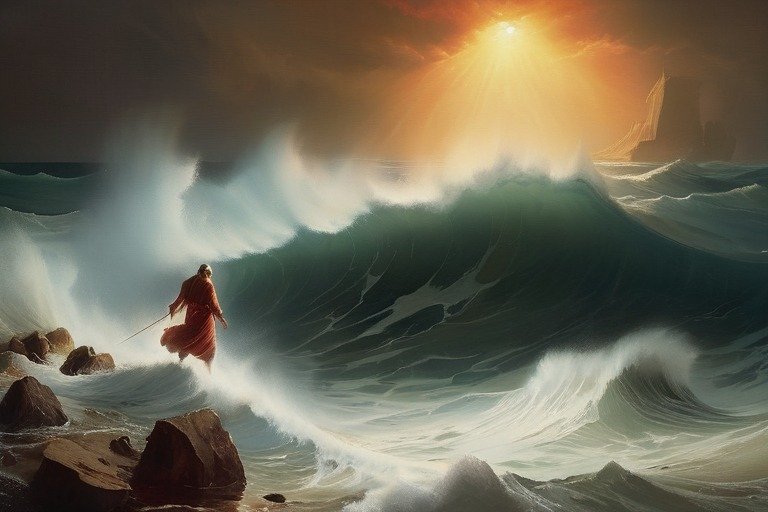

In dissecting the biblical narrative of the Israelites’ Descent and Great Exodus from Egypt, it becomes imperative to scrutinize historical archives for corroborative evidence within the Egyptian milieu.

Silent Annals: The Curious Void

The intricate series of events in this story include Joseph’s prophetic abilities, Jacob’s Hebrew family’s journey from Canaan, and the powerful plagues brought by Moses.

The deaths of Egypt’s firstborn, including the Pharaoh’s heir, and the Pharaoh’s demise in the Red Sea would logically be meticulously recorded by the knowledgeable scribes tasked with documenting daily life in ancient Egypt.

Historical Void

Curiously, the annals of the time remain conspicuously silent, bereft of any contemporaneous inscriptions documenting these momentous occurrences.

Despite the explicit duty of Egyptian scribes to record pivotal events, a void persists in the historical records about the biblical chronicle of the Israelites’ Descent and the subsequent Great Exodus.

This silence prompts a perplexing inquiry into the unspoken history, revealing an intriguing absence of documented evidence.

Inscriptions and Discoveries

Noteworthy is the discovery of the name “Israel” inscribed on a pharaonic stele, albeit devoid of any connection to Moses or the Exodus.

The Merneptah stele, dating around 1219 BC, places the Israelites in Canaan but omits any mention of their prior residence in Egypt or their departure in a monumental Exodus led by Moses.

The scientific quest for evidence regarding the Exodus encounters an obstacle, as the official Egyptian records remain resolutely silent on Moses and his followers.

Breaking the Silence: Historical Revelations

The clandestine suppression of Moses and the Great Exodus from official Egyptian chronicles eventually yielded to the pens of Egyptian historians.

Their detailed accounts, emerging from the shadows of deliberate omissions, divulge a rich tapestry of narratives surrounding Moses.

Despite an era of suppression, popular traditions endured, venerating Moses as a divine figure. The Macedonian Ptolemaic Dynasty, which succeeded Alexander the Great’s reign in 323 BC, ensured the inclusion of Moses and the Great Exodus in historical narratives.

Manetho’s Account: A Closer Look

Manetho, the esteemed 3rd-century BC Egyptian priest and historian, recorded Moses as an Egyptian figure, not Hebrew, living during Amenhotep III and Akhenaten’s reigns (1405 to 1367 BC).

The Israelite Exodus, according to Manetho, unfolded during the reign of Ramses, succeeding Amenhotep III.

Flavius Josephus, the 1st-century AD Jewish historian, preserved fragments of Manetho’s account, shedding light on a complex narrative involving divine visions, lepers, and political upheaval.

Clarification and Correction

It is crucial to correct Josephus’s assertion that Manetho invented a king named Amenophis; historical scrutiny identifies Amenhotep III as the monarch in question.

The veracity of Manetho’s account gains credence, considering the subsequent rise of Amenhotep’s namesake, Amenhotep, son of Habu, to the esteemed position of Minister of all Public Works.

Symbolic Impurity: Understanding Manetho’s Perspective

Manetho’s portrayal of rebels as “lepers and polluted people” extends beyond literal interpretation, reflecting their perceived impurity due to a rejection of Egyptian religious beliefs.

Josephus further expounds on the rebel leader’s laws, emphasizing a renunciation of Egyptian gods and customs. These oral traditions, enduring for centuries, found their written expression during the Macedonian Ptolemaic Dynasty.

Parallel Narratives: Akhenaten and Manetho’s Account

Intriguingly, Manetho’s account aligns with the historical context of Amenhotep III and his son Akhenaten, who initiated a religious revolution by abandoning traditional polytheism in favor of monotheistic worship centered on the Aten.

The parallels between Akhenaten’s actions and Manetho’s narrative suggest a historical basis for the events surrounding Moses and the Exodus.

Perspectives: Avaris vs. Rameses Dvergent

While biblical and Manethonian accounts differ on the starting point of the Exodus—Rameses in the Bible versus Avaris in Manetho’s rendition—the latter’s association of Avaris with the Asiatic Hyksos rulers aligns with archaeological findings.

Regrettably, modern scholars, influenced by Josephus’s misidentification, have often dismissed Manetho’s account as unhistorical, diverting the quest for evidence away from the historically contextual path.

Conclusion: Unraveling the Enigma

In conclusion, the enigma of the Exodus persists, intertwined with historical fragments and obscured by divergent narratives.

The meticulous examination of ancient records and a nuanced understanding of Manetho’s account beckon us to reevaluate established perspectives, potentially unveiling new dimensions to this enduring mystery.